ExplainSpeaking: How persistently high inflation undermined RBI’s effort to revive growth

The Indian Express

December 07, 2020

Udit Mishra

If inflation rate has been outside RBI’s comfort zone for the past 12 months and RBI has also bumped up inflation forecast, then why hasn’t it raised repo rates?

Dear Readers,

Exactly a year ago, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman was asked if India was facing stagflation, which refers to a phase when an economy witnesses ‘stag’nant growth and persistently high in’flation’.

The question was asked because India’s growth rate in the first two quarters of the last financial year (2019-20) had decelerated sharply to a six-year low and retail inflation — or the rate of increase in prices that we face as consumers — had shot up in November 2019.

She had reportedly replied: “I have heard of the narrative going on and I have no comments to make”. To be fair, at the time, calls of stagflation were quite premature.

For one, retail inflation had gone up for just a couple of months. Moreover, the main culprits were food prices, especially fruits and vegetable prices, which had shot up after unseasonal rains curtailed supplies.

It was hoped that before long, the “transient” spike in inflation will subside and the GDP growth will resume momentum.

But neither happened.

GDP growth continued to falter — it kept getting slower in the third and fourth quarter before Covid forced it to contract by 24% and 7.5%, respectively, in the first two quarters of the current financial year (2020-21).

The rate of Inflation remained persistently high until Covid disruption made it worse.

This brings us to the worries of India’s central bank — the Reserve Bank of India — which released its latest bi-monthly review of monetary policy last week.

The RBI is, by law, required to maintain the retail inflation rate within a band of 2% and 6%. At the start of the Covid breakout in late March and again in end-May, the RBI furiously cut interest rates so as to boost economic activity, while largely ignoring the hardening retail inflation rate. Governor Shaktikanta Das made it amply clear that the RBI will do everything in its power to revive growth.

But in the last three policy reviews, including the latest one, the Monetary Policy Committee of the RBI has decided to keep the benchmark policy interest rate — the repo rate or the interest rate at which it lends money to banks — unchanged.

For those who track monetary policy closely, this decision was a foregone conclusion even before the RBI announced it.

Why?

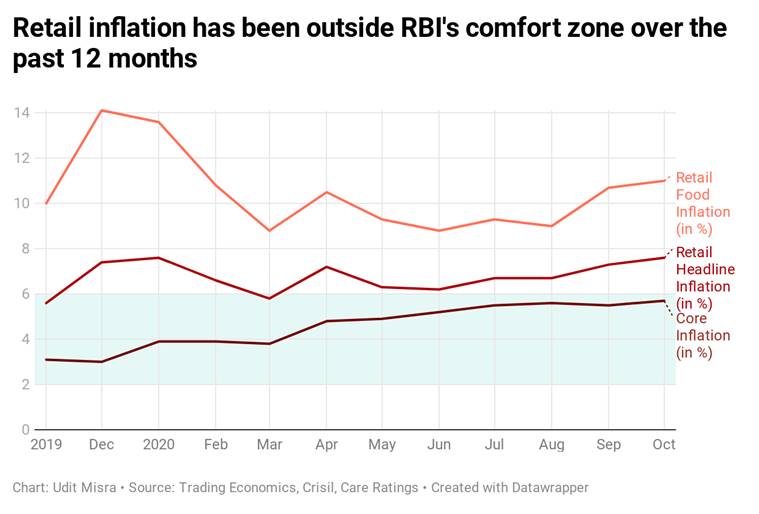

Because even though India’s economy is struggling to grow, the retail inflation rate — calculated using Consumer Price Index — had remained above RBI comfort zone for almost every month since last November (see Chart 1).

Before the December 4 policy announcement, most people believed — much like in November and December last year — that it is just a matter of time that retail inflation will come down, and when it does, the RBI will restart cutting interest rates to boost economic activity.

But here lies the most important takeaway from the latest monetary policy review: At long last, the RBI admits that, far from easing up, the inflation outlook is getting worse. “The outlook for inflation has turned adverse relative to expectations in the last two months,” stated the policy statement. As a result, the RBI has substantially raised its inflation forecast not just for the current quarter (October to December) but also for the two quarters after this one — January to March and April to June in 2021.

Look at Table 2. It is taken from RBI’s latest “survey of professional forecasters on macroeconomic indicators”. The figures in parenthesis show the extent of revisions. As can be seen by a sea of plus signs, forecasters have bumped up inflation forecasts across the board — be it retail or wholesale, headline or core, this quarter or two quarters hence.

Retail inflation has been outside RBI’s comfort zone over the 12 months

Retail inflation has been outside RBI’s comfort zone over the 12 months

Comments

Post a Comment