From Bihar to Andhra, how India fought, and won, its 50-yr war with Left-wing extremism

The Print

June 27, 2019

Niranjan Sahoo

he Maoist movement in India is among the longest and most lethal homegrown insurgencies that the world has seen. While the origin of Left-Wing Extremism (LWE) in the country goes back to the Telangana peasant rebellion (1946-51), the movement took the young republic by storm in 1967. On 25 May that year, peasants, landless labourers, and adivasis with their lathis, arrows and bows undertook daring raids of the granaries of a landlord at the Naxalbari village of West Bengal.

The rebellion, quelled by the police in a matter of a few days, gave birth to what would be called the Naxalite movement (named after the hamlet) led by the charismatic Charu Majumdar and his close associates, Kanu Sanyal and Jangal Santhal.

The arrest of Charu Majumdar in 16 July 1972 and his subsequent death in police custody some days later prompted analysts to pen obituaries for the Naxalite movement. Within a decade, however, the movement made its presence known in other regions of the country.

The merging of the Communist Party of India (Maoist-Leninist), the PWG, Maoist Communist Centre of India (MCCI) and 40 other armed factions into the Communist Party of India (Maoist) in 2004 turned the tide in favour of the insurgents.

The movement would eventually spread across such a vast geography that it surpassed all other insurgent activity including those in the Jammu and Kashmir and the Northeast. At their peak, the Naxalites were dominating in more than 200 districts across the country, prompting then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in April 2006 to call the Maoist movement “the single biggest internal-security challenge ever faced by our country.”

A key to the Maoist movement’s growth was the expansion of its financial base. By the late 2000s, coinciding with the spread of their geographical influence, the amount of financing in the hands of the Naxalites had reached some Rs 1,500 crore (approximately US$ 350 million).

State response: An analysis of seven states

Given that law and order is under the purview of the states or provinces, the most crucial counter-insurgency efforts are in the hands of state-level leadership. The federal government supported these efforts with joint strategies, resources, intelligence and coordination.

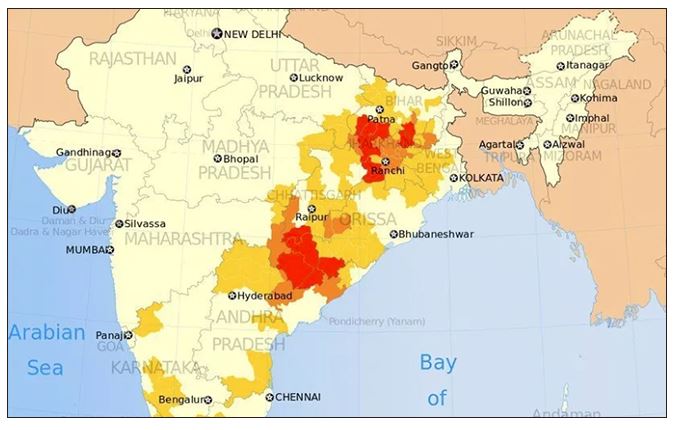

Current spread of CPI-Maoist

Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh (undivided), which witnessed the rise of the Maoist insurgency in the early 1990s, is often showcased as a success story in counter-insurgency. The PWG faction had dominated 20 districts of the State.

Following the attack in 2003 on then Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu, who narrowly escaped, Andhra Pradesh embarked on a rapid modernisation of its police force while ramping up its technical and operational capabilities.

The state also quashed mass organisation activities through the use of civilian “vigilante” groups that it had carefully encouraged through an attractive Surrender and Rehabilitationpackage.

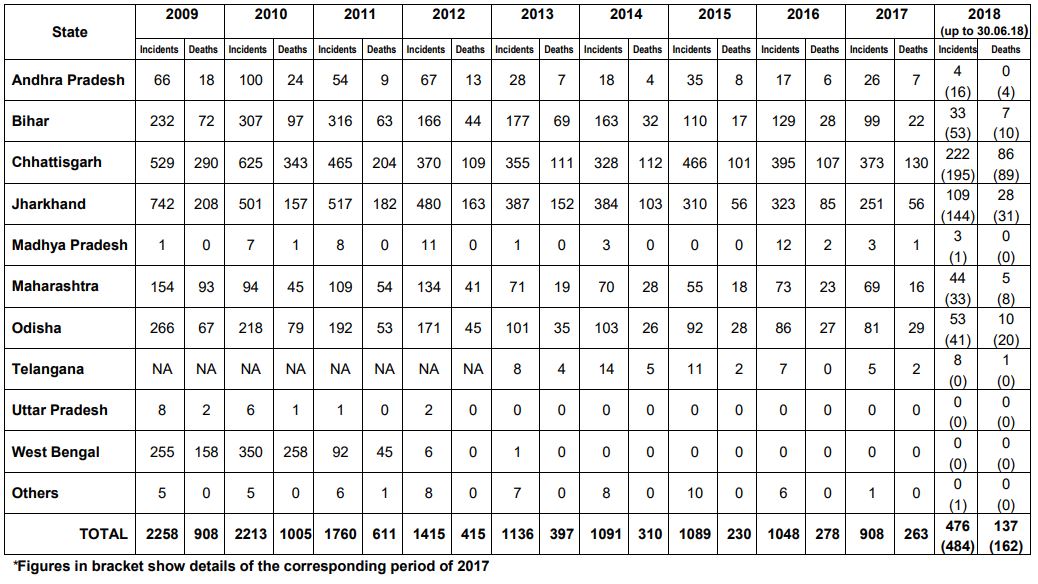

Andhra Pradesh succeeded in stamping out Left-wing extremism by combining police action with socio-economic programmes implemented by an effective service delivery mechanism (Table 2).

Chhattisgarh

Chhattisgarh is today considered the epicentre of Maoist insurgency in India. At their pinnacle, the Naxalites had influence over as many as 18 districts in the state, out of a total 27. Indeed, beginning in the late 1980s, the 40,000-sq-km Bastar region—made up of the Dantewada, Bijapur, Narayanpur, Bastar and Kanker districts—became the nerve centre of Maoist militancy in India.

Nearly 25,000 sq km of Bastar (including Abujmar, the Maoist citadel of the so-called Red Corridor) are believed to be intensively mined by Maoists. While Maoist-led violence remains a major concern in Bastar division especially the northern parts, significant progress has been made in restricting Maoists to the state’s southern districts (Table 2).

The game-changer seems to have been the improved road connectivity: 11 key road projects were finished by 2018, connecting the Sukma, Bijapur and Jagdalpur districts. To be sure, however, the Maoist threat remains a serious concern for the state. As a sort of warning, as recently as April this year, the insurgents conducted an attack in Dantewada that killed the incumbent BJP MLA and his four security personnel.

Jharkhand

At their height in Jharkand in the late 2000s, the rebels had a sway in as many as 20 districts across the state. Then Chief Minister Shibu Soren was of the view that the insurgents were “misguided” youth who can be persuaded to re-join society, and initiated a peace dialogue. The talks collapsed, however, in 2010 and then Home Minister P. Chidambaram issued orders to Soren to step up on state response.

That same year the Jharkhand government formed a special force (the Jharkhand Jaguar modeled after the Greyhounds of Andhra Pradesh) to lead the anti-Naxal operations. The state government also framed a unique surrender policy for Naxalites. Together with central forces, the state launched Operation Anaconda to weed out Maoists from Saranda and succeeded in 2011.

After the BJP won the state elections in December 2014, the new Chief Minister Raghubar Das began various counter-insurgency initiatives. In the last few years, the number of Maoist-related violence—reaching its peak in 2013 with 480 incidents—has declined to 53 in 2018. The year 2018 recorded the lowest number of Maoist violence-related fatalities (Table 2).

There has also been a high number of rebels who surrendered — as many as 108 in 2018 alone. This is not to say that Left-wing extremism has been completely eliminated in Jharkhand. There remain several active rebel hotspots across the state’s vast terrain.

West Bengal

West Bengal, the birthplace of the 1967 Naxalite uprisings, witnessed an unprecedented rise in Maoist insurgency a decade ago. By early 2000s, the CPI-Maoists had spread over as many as 18 districts of the state.

Beyond Lalgarh, the Naxals played a critical role in fuelling agitations in Nandigram and Singur, which would subsequently lead to the defeat in the 2011 polls of then three-decade Left government in the hands of Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress party.

While in the opposition, Banerjee and her party allegedly built a tacit understanding with underground Maoists; once in power, she changed her approach especially as the insurgents began targeting her supporters and key party leaders in their stronghold, the Jangalmahal region.

The government under Mamata Banerjee changed the piecemeal approach of the Left government and adopted a three-pronged counter-insurgency strategy. First, the government overhauled the security strategy by setting up an elite police team to pursue the rebel leaders. Second, they offered a surrender and rehabilitation package to the rebels, promising jobs and entrepreneurial opportunities to those who would surrender. The third and perhaps most critical element of the campaign was in the form of comprehensive confidence-building measures with the people living in the Maoist-infested Jangalmahal region comprising the districts of Purulia, West Midnapore and Bankura.

From a peak of 425 Maoist-related violent incidents in 2010 (which killed 328 civilians and 36 security forces), the number came down to zero by the end of 2018. According to a report issued by the state government, more than 250 Maoists have surrendered before the state police between 2014 and 2018. There is one district, Jhargram, that remains categorised as “highly affected” by the insurgency.

Odisha

At one point in the late 2000s, the Maoist influence stretched over 22 of the 30 districts of Odisha. The hotspots of Maoist activities were the most backward and forested, mineral-rich districts with huge adivasi populations—i.e., Koraput, Malkanagiri, Nabarangapur, Rayagada, Gajapati, Kandhmal and Ganjam and Keonjhar.

The insurgents also fuelled protests against several mega projects on the issues of land acquisition and mining rights, particularly in the recent Niyamgiri and POSCO projects.

The Nayagarh incident in 2008 jolted the lackadaisical state administration to the Maoist threat. The same year, the insurgents launched a brazen attack in Balimela near AP-Odisha border, killing 37 Greyhounds soldiers. These two incidents left Odisha’s leaders with no illusion about the expanding Maoist footprint in the state.

They immediately fortified the police stations, gave police officers rigorous training, and announced a suitable incentive package to police personnel involved in anti-Maoist operations. Importantly, thousands of tribal youth from the insurgency-affected areas were recruited as Special Police Officers (SPOs). The State also opened a training school in each of the seven police ranges, supplemented by 17 battalions of Central forces stationed in key Naxal-affected districts.

Over time, Odisha achieved significant progress in managing Left-wing extremism especially in the mineral-rich regions.

Statistics show that there has been a steady decline in the number of Maoist-related incidents in Odisha (See Table 2). Maoist-related fatalities dropped from 42 reported in 2016 to nine in 2017, when security forces killed several key Maoist leaders. Between 2015 and 2016, more than 1,000 underground Maoists surrendered. Today, eight districts remain “worst-affected”—i.e., Malkangiri, Koraput, Kalahandi, Kandhamal, Rayagada, Bolangir, Bargarh and Angul. State officials, however, declare that rebel influence is restricted to only some pockets of the bordering districts of Malkanagiri and Koraput.

Bihar

At their peak in 1980s, the Maoists in Bihar enjoyed widespread support among the poor and oppressed classes and carried out their agenda through various means. What sustained the insurgency was Bihar’s failed land reform—which left much of the land in the hands of the upper-castes, fueling caste feuds where the rich employed the services of private militia like the dreaded Ranvir Sena and took advantage of a weak state that failed to provide order.

The consolidation of Maoist forces helped the CPI-Maoist to expand to new areas as well. Beyond their traditional strongholds in Patna, Gaya, Aurangabad, Arwal Bhabhua, Rohtas and Jehanabad in southwestern Bihar, the rebels spread their base to North Bihar, bordering Nepal, in the early 2000s.

It was Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, assuming power in 2005, who took credible steps to restore law and order in Bihar.

On the security front, the Kumar government initiated a number of steps including the creation of a 400-member Special Task Force as well as a Special Auxiliary Police for counter-insurgency. The state government revamped its surrender and rehabilitation policy to make it more attractive for insurgents to lay down their arms.

What has perhaps yielded the most significant results was a series of development and good-governance measures adopted by the Kumar government.

CM Kumar’s efforts have been branded as “effective politics”. Naxal-related fatalities that reached their peak in 2011 came down to more manageable levels (Table 2).

While the state saw as many as 22 of its 38 districts fall under Naxal influence, the count has since gone down to four—i.e., Gaya, Jamui, Lakhisarai and Aurangabad. Last year, the insurgents killed 10 CoBRA commandos and injured an equal number in an attack in Aurangabad district.

Maharashtra

Maoists currently hold influence, in varying degrees, in Maharashtra’s districts of Gadchiroli and Gondia, which have areas contiguous with the Dandakaranya region of Chhattisgarh.

Compared to several other Maoist-affected states, Maharashtra has responded rather seriously with a slew of measures comprising both security and developmental components. For example, the State has launched major offensive operations against the Maoists in the Gadchiroli-Chhattisgarh-Andhra border.

Further, the state administration is working to strengthen the police machinery in Gadchiroli and other Naxal-affected areas in terms of providing specialised training, as well as more funds for modern weaponry and equipment. The state has also created a district-level force, the C-60 commando, which has received appreciation from top officials of the Centre.

Similarly, the government has put in place a Surrender and Rehabilitation Policy to encourage Maoist cadres to re-join society. The state government has also taken some controversial decisions in its effort to break the back of the Maoist movement. For example, state forces have arrested and prosecuted individuals that they have identified as Maoist “sympathisers”, giving them the pejorative name, “urban Naxals”.

These individuals, according to civil liberties activists who are critical of the state government’s moves, are mostly academic scholars and NGO workers.

The state police along with Central paramilitary forces have succeeded in killing scores of rebels and arresting hundreds of them in the last few years. There was a single instance of security forces killing 39 rebels. In short, the Maoists in Maharashtra are on the run (See Table 2). The surrender policy is also showing positive results. In the last 12 years, more than 500 rebels including several prominent leaders such as spouses Rammana and Padma Kodape have surrendered to the state police. The Maoists remain visible, however, in adivasi-dominated districts, particularly Gadchiroli. They are still able to launch attacks in their stronghold; amongst them was the recent violence in Gadchiroli where 15 security forces were killed.

The Centre’s Response

The Centre’s response to Maoist insurgency has followed a similar pattern as those of the different states. Yet, given that India is a federal country and the subject of law and order is vested in the states, the Union government has largely led the counter-insurgency efforts from behind.

Successive governments at the Centre have provided the resources—security and financial, paramilitary, intelligence and strategic direction—to find sustainable solutions to the Maoist insurgency.

While the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) governments between 2004 and 2014 laid down the building blocks for India’s anti-Maoist response, the current National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government has accelerated its pace. On the whole, UPA and NDA governments at the Centre have adopted a mix of methods—population-centric and enemy-centric—to quell the Maoist movement. The overall aim has been to complement state initiatives.

The law and order approach

The law and order approach continues to be the key pillar of the Centre’s counterinsurgency strategy. This is best exemplified by the deployment of 532 companies of central paramilitary forces in the affected states.

In 2006 the Central government under then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh for the first time issued a security blueprint to tackle the Maoist threat. The blueprint was prominently featured in the government’s 14-Point Policy and subsequently took the form of a series of security-centric measures to address the growing Maoist movement.

- Modernisation of police forces

- Strengthening intelligence networks

- Aiding states in security-related infrastructure

- Deployment of central paramilitary forces

- Special infrastructure scheme

- The NDA government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s launch of SAMADHAN scheme in May 2017.

- Ban on the CPI (Maoist) and the UAPA Act, 2009

- Strengthening monitoring and coordination mechanisms through a series of steps, including the creation of a Unified Command.

Development programmes

The Centre initiated a series of development and good-governance measures to deny the insurgents the support of the affected populations.

This approach was best illustrated in the Union government’s appointment of an expert committee (headed by D. Bandyopadhyay, the architect of “Operation Barga”) to carry out a detailed study of socio-economic developments in the affected regions and suggest measures to address these deficits.

Following the suggestions of the Expert Committee and the government’s own assessment of the situation, an unprecedented amount of resources were transferred to areas affected by the Maoist insurgency. One of them is the flagship Integrated Action Plan (IAP) launched by the UPA government to implement a special scheme which addresses the development deficiencies in LWE-affected districts; the financial package was over INR 6,000 crore per annum.

While the NDA government has disbanded IAP scheme, it has come out with its own scheme called Special Central Assistance (SCA) to cover 35 most LWE-affected districts.

The most significant steps taken by the Centre are in terms of enacting few landmark legislations recognising the rights of adivasis to access forest resources and for self-governance. The passage of Forest Dwellers Act in 2006 despite stiff resistance from environmentalists and NGOs is a clear statement of the Centre’s resolve to address the grievances of tribal populations living in the Naxal-affected areas.

Outcomes

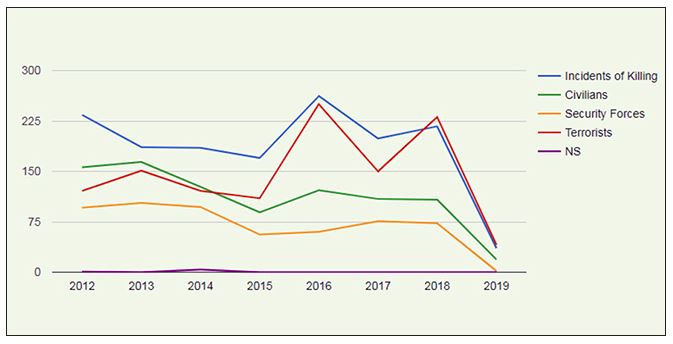

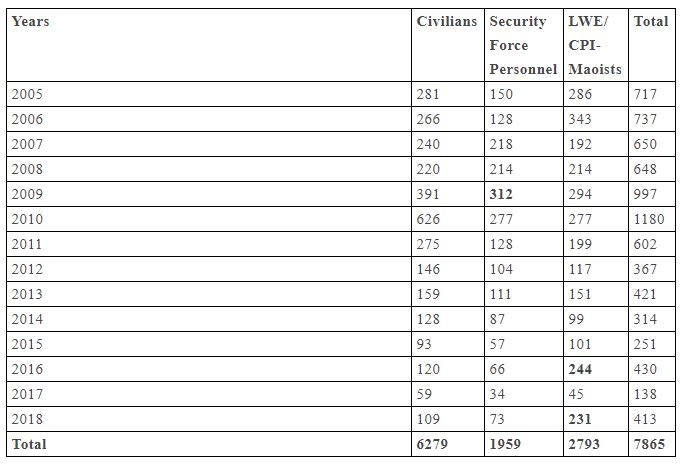

The outcome of a coordinated COIN is telling (See Chart 1, Table 1). Coordinated and concerted efforts from the Centre and Maoist affected states have brought down Maoist sponsored violence to drastic levels, have resulted in elimination of many important leaders of the insurgent organisation, and reduced their dominance to a handful of tri-junction districts in Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Odisha. This is evident when the MHA removed 44 districts from Naxal affected list, while the ‘worst-affected category’ was reduced from 36 to 30.

Chart 1: Rapid decline in Maoist-related fatalities

Yet, what is more noteworthy is that security forces in the recent years have achieved the seemingly impossible by eliminating many top leaders. Security forces have also succeeded in neutralising as many as 26 prominent members of 39 Central Committee in the past two years. They have captured more than 7,000 active cadres in the last three years, while an equal number of Maoists have surrendered before authorities in various states. In 2016 alone, security forces arrested as many as 1,844 CPI-Maoist cadres, while more than 1,442 members of the group chose to surrender before the state authorities.

Table 1: Fatalities in incidents of Maoist violence (2005-2018)

Table 2: Naxal violence by state: Incidents and deaths (2009-2018)

After more than 50 years of its existence and dominance in various stages, the Left radical movement appears a spent force, restricted to a few hilly districts of three bordering states. A combination of improved state actions, change in political economy and internal churns within the organisation have seriously hobbled the insurgency. Loss of strongholds, declining appeal of ideology and leadership crisis, along with improved performance from the affected states on socio-economic fronts, may make it difficult for the insurgency to regain the momentum it once had decades ago. The final death knell would come from significant improvements in security agencies, particularly the police forces, improved security and intelligence infrastructure, and better command and control system to keep track of the rebels and their movements.

Conclusion

After many years of indifference, half-steps and ad hoc measures, both India’s central and state governments have found their foothold against the Maoist insurgency that at its pinnacle may have seemed invincible.

Upon realising that the Maoist movement was thriving in the lack of state presence in large parts of central India mostly inhabited byadivasis in hilly and forested terrains, state agencies began to show alacrity and serious purpose in making up for such prolonged absence. The state restored the rights of indigenous communities, particularly the adivasis, over land (also ending an arbitrary land acquisition policy that rendered millions homeless in 2013 with a new legislation), forest and natural resources; distributed land records (pattas); reformed the justice delivery systems; and rolled up attractive surrender and rehabilitation schemes. The state aimed, and succeeded to a significant degree, to puncture the Maoist narrative of “an exploitative state run by the bourgeoisie”.

Is this then the end of a protracted insurgency that has been clouding the Indian state in some form or another since the Naxalbari rebellion? Some analysts argue the contrary—that despite losing vast territories, large cadres and several top leaders, the CPI (Maoist) remains a formidable force. They cite as proof the daring attacks by Maoists in recent times.

While it may be undeniable that the Maoists still have the strength to make their presence felt in certain regions, it would be grossly untenable to say that they continue to pose an existential threat to the Indian state as they did in the late 2000s.

This analysis shows that Left-wing extremism in India is in terminal decline. Not only has the ideology of revolution lost its old appeal (evident in the lack of interest among locals to join the militia), an improved performance from the state on the development and governance fronts makes it difficult for the insurgents to grow in the same manner as they managed at their peak. The Maoists could continue as a fringe group with the ability to launch sporadic but violent attacks and disrupt governance in their areas of dominance.

Comments

Post a Comment