Non-Performing Assets: When and how did banks pile up such bad loans?

The Indian Express

September 14, 2018

September 14, 2018

P Vaidyanathan Iyer

India choked when the Lehman Brothers collapse struck the US on September 15, 2008, and triggered a global financial crisis. It’s going to be 10 years, and despite a rebound in India’s GDP growth in April-June 2018, the macros look stressed. The rupee continues to slide, having lost over 13% since January 1 this year, and the current account deficit has widened to 2.4% of GDP in the in the quarter ending June 2018.

The biggest of all problems — non-performing assets of banks — continues to grow. When and how did banks pile up such bad loans?

To trace its origin, let’s rewind to the halcyon days of 2005-08. The India Shining campaign of the previous NDA government (1999-2004) did not bring electoral gains to the BJP, but at the end of Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s term, the economy stood primed for unprecedented growth rates touching double digits in the coming years.

The UPA government’s fiscal discipline during 2004-08, until Lehman struck a body blow to the global economy, was exemplary. By the end of this four-year period, the Centre’s fiscal deficit had been dramatically curtailed, and brought down to 2.7% of GDP.

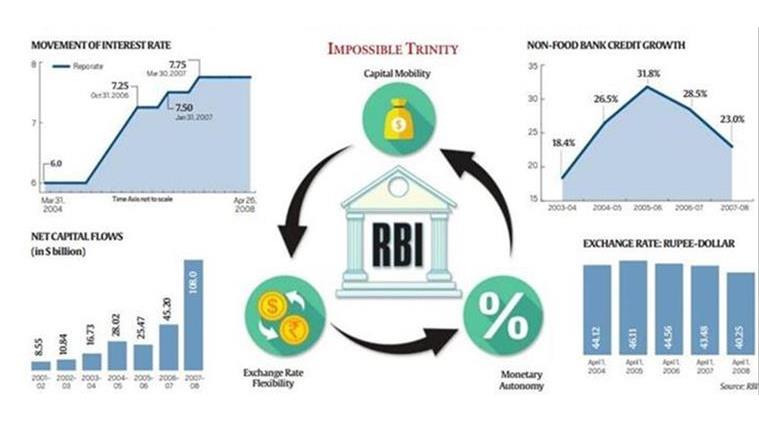

On the monetary side, the ride was tricky, and posed many challenges for the Reserve Bank of India under Yaga Venugopal Reddy. The central bank, which is the banking regulator as well as the monetary authority, was trying unique ways to manage the ‘impossible trinity’, a challenge that countries across the world have struggled with.

The impossible trinity or ‘policy trilemma’ derives from the Mundell-Fleming model, which holds that a country cannot at the same time have monetary policy autonomy, a fixed exchange rate, and free capital movement; it has to choose any two of the three, hence the trilemma. India, a developing economy, wants capital, an exchange rate that favours exports, as well as monetary policy independence to keep a check on inflation. Its attempt to manage this had limited success and some unintended consequences.

Capital flows to India were rising steadily from the early 2000s onward. From $17.3 billion in 2003-04, net capital flows jumped over six times to $107.9 billion in 2007-08. In calendar year 2007, India received $98 billion, the third highest in the world after the US and Spain, and the most among emerging market economies. Despite measures to deal with capital flows, India could not control the surge, and RBI intervened to sterilise, or sell, government bonds in its stock.

The sterilisation intervention works this way: RBI buys dollars coming in via capital inflows by releasing rupees. This, however, results in huge rupee liquidity with banks, which will in normal course chase existing bonds, driving bond prices up and pushing yields down (bond prices share an inverse relationship with yields). Lower yields are bound to force RBI to cut policy rates. If RBI wants to avoid reducing rates, it sterilises the liquidity resulting from dollar purchases by issuing fresh government bonds.

So far so good. But the RBI ran out of its stock of government bonds by 2004, and had to issue fresh paper (called MSS or market stabilisation scheme) bonds. This brought fiscal costs — and the Finance Ministry, which had to pay interest on these bonds (Rs 8,400 crore in 2007-08), resisted after a few years. Given rising interest expenses and the Ministry’s objections, RBI could undertake only partial sterilisation post 2004, which led to compromises in monetary policy autonomy.

Such massive inflows would also lead to a sharp appreciation of the rupee. But instead of allowing the exchange rate to fluctuate based on market forces, RBI would intervene heavily in the foreign exchange market by purchasing excess dollars, leading to an accumulation of reserves. The RBI kept the exchange rate rigid, at a time when capital flows surged. This helped avoid any adverse impact on exports, on the back of which the Indian economy rode and posted growth rates of 8-9 per cent.

Since only partial sterilisation was possible through the issue of MSS bonds after 2004, the banking system was left with significant rupee liquidity. The quantity effect ensured that the pricing remained low, as was reflected in the inter-bank rates those days.

This spilled over into monetary policy interventions, which kept interest rates low and laid the foundation for a credit boom during 2004-05 to 2007-08. Given past experience with infra projects that were completed on time and within budget, banks lent heavily.

Lending by banks to industry (excluding individuals, agriculture and Food Corporation of India) jumped 30-35% year-on-year during this period, making this boom the biggest in 25 years in India. The phenomenal lending needs to be seen in the context of a developing economy long starved of credit. Credit growth could not be stopped; it would have been detrimental to growth. India was being catapulted into a high growth orbit, and the idea probably was to preserve the moment.

The RBI under Reddy was also balancing multiple objectives: regulating banks, reining in inflation, managing government borrowings, promoting growth, and ensuring financial stability. Many balls were up in the air, and not one could be allowed to crash. Enormous faith was being placed on the due diligence capabilities of banks, and there was a general belief that the prudential norms of banks were foolproof. This, of course, can never be true.

In his recent note to Parliament’s Estimates Committee, former Governor Raghuram Rajan pointed out that a large number of bad loans originated during 2006-08 when growth was strong. “It is at such times that banks make mistakes,” he said. The credit boom, and the phase of irrational exuberance, is a problem that pre-dates Lehman, but the jolt of the financial crisis, the fiscal policy mistakes that followed, poor coordination among regulators, and the wrong lessons learnt, continue to dog India.

Comments

Post a Comment